Driverless cars can change our urban world

By David Janner-Klausner | 13/01/15 16:00

4 min read

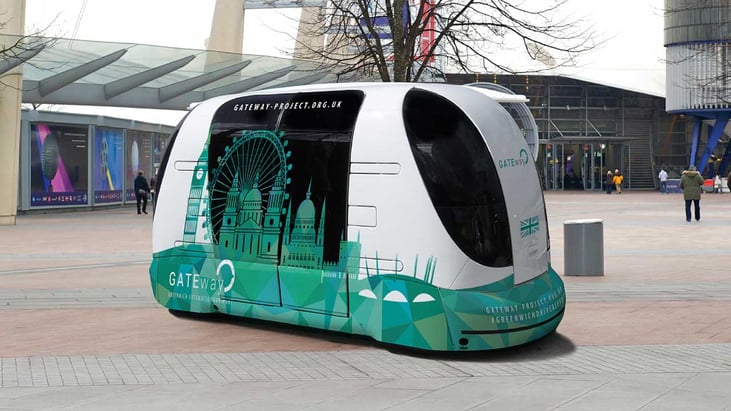

How do you feel about driverless cars? Commonplace is part of a consortium that will be testing driverless cars in Greenwich, starting later this year. Our role will be to gather information on how these new vehicles make people using them and around them feel, and what are the immediate reactions of pedestrians, cyclists, other drivers and passengers in the driverless vehicles to this new specimen of urban infrastructure.

Technological, legal and ethical challenges abound. “Big Data” is part of this, of course. The capacity to process, store and analyse massive amounts of data that has grown exponentially in recent years. This mean that the cars and the data system around them can be more responsive and adaptable. Huge amounts of data will be generated by multiple sensors on the vehicles, signals from the road and other factors and translated via algorithms to vehicle behaviour which will be efficient and safe. Acceptance will depend on how safe the vehicles are in practice and how safe they are perceived to be, and how they fit in with the urban fabric.

Current research on attitudes to driverless vehicles - before anyone has encountered them on public roads - shows mixed reactions. Last week, comparison site uSwitch published the results of an on-line survey about the acceptability of driverless cars. It was based on just under 1,000 participants, and while it does not claim to be a representative sample, it still offers an interesting baseline for attitudes before people encounter driverless vehicles in reality. Headline findings are:

- 48% of consumers would be unwilling to be a passenger in an autonomous vehicle.

- Four in 10 (43%) wouldn’t trust a car to drive safely without a driver and 16% say they are ‘horrified’ by the idea.

- Almost a fifth (19%) see the introduction of autonomous vehicles as a positive move to help solve pointless hold-ups and tedious traffic jams and a further fifth (18%) are excited about the technology featuring on Britain’s roads in the coming years.

- An overwhelming 92% of consumers feel in the dark about the trials while just 6% believe the Government is running sufficient tests.

- Over a third (35%) expect the introduction of driverless cars to drive up their insurance premiums.

- Consumers confused over car accident liability, with a quarter (26%) believing fault lies with the autonomous car manufacturer.

An international survey by a team at the University of Michigan, conducted earlier last year, reported similar results for the UK, and much higher acceptability in other countries:

They found that about 87 percent of respondents in China and 84 percent in India have positive views regarding autonomous and self-driving vehicles, compared to 62 percent in Australia, 56 percent in the U.S., 52 percent in the U.K. and 43 percent in Japan. Half of the Japanese respondents were neutral, while the U.S. registered the highest percentage of negative views (16 percent) among the six countries.

Source: Self driving vehicles generate enthusiasm concerns worldwide

Given that 92% of respondents to the uSwitch survey feel “in the dark”, an approximately 50/50% split of opinion may actually be seen as a tribute to the open-mindedness of the respondents. The figures also point to the critical importance of the trials in providing real-life experience - and to the importance of Commonplace’s role in capturing the nuances of these experiences and communicating them.

If the vehicles eventually prove feasible and acceptable, their urban consequences are potentially radical. Driverless vehicles offer a combination of on-demand travel of the private car, but with unprecedented efficiency. The car can take you to work, then proceed to run several other errands, returning to collect you when you need it. It needn’t even be the same car all the time. So personal mobility can be decoupled from ownership - something traditionally offered by cabs at a very high price, or by car club schemes that offer some of the convenience of a private car without ownership. Compared with either, driverless vehicles offer the convenience of the cab without the cost of the driver, and are superior to car clubs as the vehicle will come to you - rather than having to find stands from which to collect and to return the car to.

Driverless is also ideally suited to electric propulsion - the best solution for highly congested areas as there are no tailpipe emissions. When the battery runs low, the car can take itself to a charging point and charge enough to handle the next set of journeys, optimising drive and charge timings.

What this means is that in certain locations and times of day, the same number of journeys can be serviced by considerably fewer vehicles, possibly achieving a holy grail of relieving urban congestion - fewer vehicles needed for the same number of journeys. This can potentially free up road space to encourage more cycling, walking and street activities - improving quality of life, health prospects and air quality.

The challenges to realising this vision are formidable. There are technical challenges, which the trials - our project in Greenwich is one of a cohort of four around the country - will bring to sharp relief and help solve (1). There are legal challenges - what is the liability and accountability envelope of a driverless vehicle? But assuming these are overcome, there will be a political challenge - to leverage the potential to de-clog cities for common long-term good, rather than see the road space freed squandered on encouraging other motorised transport. This is the classic pattern - build more road capacity and people are attracted back to driving with the promise of a shorter journey time. Unfortunately, when many drivers set off with this new hope, the extra vehicles soon slow the traffic back down. Capping and reducing car ownership and use requires a great deal of political will, but driverless cars may offer an attractive way forward for the sustainable urbanism faction. However, the industrial jobs faction will rightly be concerned that the efficiency of driverless vehicles will lead to a drop in demand for cars and pressure on an industry that provides huge employment and revenues.

All of which takes us to a wider conversation about how society re-organises to absorb the impact of automation. We have seen automation generate changes that remove layers of management and many traditional processing jobs in manufacturing and services. We have seen it remove the need for tram drivers on the Docklands Light Railway. And now we could see urban mobility require fewer vehicles and drivers. The next few years will see society confronting the question of how to fairly distribute the opportunities to earn a living through work as traditional labour markets hollow out. What Commonplace will measure and communicate in Greenwich is just one visible part of a large and complex iceberg.

###Footnote (1) The trials will be conducted by three consortia, and as well as in Greenwich will take place in Milton Keynes, Coventry and Bristol.

###Sources uSwich press Release

University of Michigan announcement of research findings

Journal report on University of Michigan research, with additional detail on UK respondents

.png)