Our company, Commonplace has recently completed a seed funding round to support further development of our digital product for developers, which helps them collaborate more effectively with local people about their proposed schemes. The funding included investment from Clearly Social Angels, a social-impact focused angel group.

But why would a developer want to open up a public debate about a prospective development? And how can they benefit by adopting a more transparent approach with the help of new technology?

In the UK, informing the public about forthcoming development is mandatory but the level of engagement that is actively courted varies a great deal. There is certainly a traditional view, held by developers and some public authorities, that advocates the minimum required engagement with the public. Details of a plan tend to be primarily developed with public officials who are custodians of “The Planning System”. Of course, elements of this approach are essential – there is every reason to work with the planning authority to ensure that plans meet local policy frameworks and aspirations.

Implicit in this traditional arrangement is the idea that public interest is best mediated by planning authorities. However, the legitimacy and effectiveness of “The Planning System” is being challenged from a number of directions. The arc of this challenge ranges from the objective pressure to develop housing to keep up with the growing population, through a vigorous debate on what makes sustainable communities – environmentally and socially, and on to the balance of power between local communities, local government and central government, for example through the Localism Act.

These challenges are being expressed and mediated not only through traditional channels of communication, but increasingly through digital and social media as well. Herein lies the first new dilemma for developers: the public are debating their plans on social media whether or not they like it – or take part in the conversation. Should they engage, monitor or ignore these discussions?

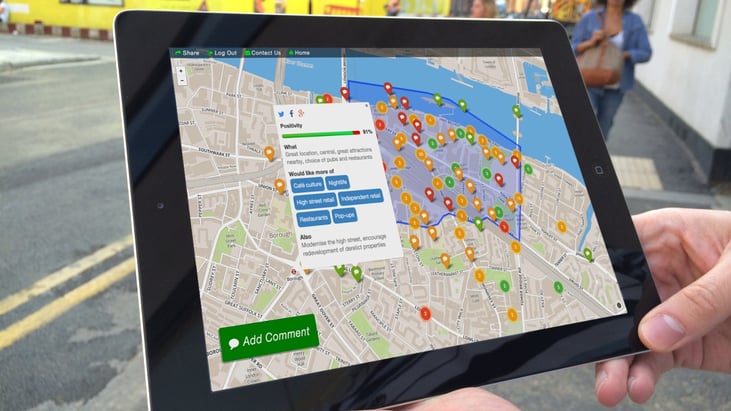

New digital tools are evolving to facilitate debate about the built environment. A virtual arena is flourishing alongside the traditional interaction between communities, planners. politicians and developers. These tools (which include Commonplace) offer developers the opportunity to get on the front foot in their interactions with the public – and establish a new paradigm of transparency and collaboration with the public, which ultimately benefits their businesses as well as local communities.

How is this new public arena evolving and what does its existence mean for public engagement in the built environment?

Broadly, the tools of the digital arena fall into three categories, each disruptive of the status-quo in a different way, covering an evolution from information through interaction to engagement:

- Informing the public of processes and forthcoming decisions. The foundation of changing engagement has been ease of access to procedural information. Local authorities publish agendas and details of planning proposals and applications on-line. There are tools for the public to receive real-time notification of any proposed local development provided by local authorities and commercial site http://www.planningfinder.co.uk/which lists planning applications in a searchable web site. http://www.planningportal.gov.uk/ contains information about the planning system and tools for lodging planning applications on-line. The recent “Right to Report” legislation, allowing anyone to digitally report from public meetings, is a further step towards transparency.

- Tools for interacting with decision-makers. Decision-makers are easier to find and communicate with than ever. The humble email gives instant access. Emailing is made easier by web sites such as https://www.writetothem.com/ which provides details of elected leaders by postcode – national and local. Local social media such as Streetlife, hyperlocal websites like Westhampsteadlife.com and Facebook are used to communicate and organise concerted campaigns on local planning issues. Twitter can create a wave very quickly and engage younger people with local issues. While these tools are external to the planning system, they impact on the decision-making process, raising dust in the arena where diverging interests compete.

- Tools for engaging in plan making. A new category of web-based tools is coming onto the market that seeks to engage local people in helping shape plans for their localities. These tools are attempting to address the multiple challenges to the planning system – the fact that more and more people want to engage with local decisions, yet are frustrated with the established ways of doing so. This frustration manifests itself in the declining turnout for local elections (and elections in general) especially by young people. But the same citizens who refrain from voting are more active than ever on-line. Commonplace falls into this category.

The opportunity is to build a bridge between lively and growing online engagement and the deficit in formal local engagement with communities. There are significant prizes for the developers that embrace increased transparency and collaboration: greater trust, reduced planning risks, more balanced views from across the community, and development of a beneficial long-term relationship with communities as well as the planning authorities.

Developers should be at the forefront of building this bridge. Planning applications perceived to be agreed between local authorities and developers to the exclusion of the public can fail expensively through a concerted social media campaign – yet the participants in such a campaign may not be representative of wider opinion. The remedy is not to try and preserve the traditional order by ignoring social media, or by continuing adversarial process within it.

Our reason for creating Commonplace was a belief in the need for a more collaborative tool, a neutral and open platform where local opinion, sentiment and ideas can be obtained and shared. This may sound idealistic, but really it is a hardnosed response to the new rules of engagement (pun intended). Smart Cities will be inhabited by smart citizens, and will required smart developers to engage with their needs. The smartest developers will be those using this opportunity to benefit their business models.

.png)