I spent part of the weekend reading LGIU’s new report, “Technology and Transformation in Town Halls”. LGIU (Local Government Information Unit) is an influential think tank (disclosure – I worked there for several happy years in the mid-noughties) and I’m always interested in what its people are saying. This report, sponsored by HP, looks at three dimensions of technology in town halls – efficiency, engagement and empowerment.

Commonplace fits naturally into the “engagement” section, so I gravitated towards it. The authors point to the availability of information about how well (or not) local services are functioning. This, they argue, leads to greater transparency and accountability:

Rather than merely suspecting a neighbouring borough receives a better local service, one can compare, contrast and prove this. Citizens can compare schools, care provision, bin collections and gauge how their local council is performing.

That is useful but still, arguably, a “consumerist” approach to engagement – it creates levers to engage with the local authority, but is not yet an example of engagement in setting priorities and in decision-making. To help delve deeper, the authors pose this test-question for new technology:

Do emerging technologies go beyond better communication and actually helping to forge a new collaborative relationship between citizens and state?

The question is spot-on, and its ramifications are potentially highly disruptive for the existing model of local representative democracy. The report’s examples of collaborative platforms don’t reflect this challenge directly, however – Wikipedia is mentioned (although it does not impact directly on political discourse) and several commercial “collaborative” sites are cited – Airbnb and Uber. The issues that Uber places before local elected politicians responsible for cab licensing are not mentioned, which is a shame. Uber is a live example of how a disruptive technology challenges an existing operating regime and the politicians responsible for it.

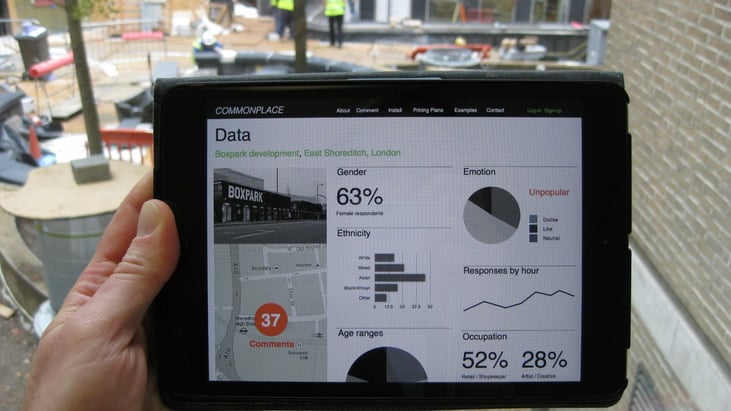

I’d have welcomed a wider discussion of how what I call “ongoing democracy” can be facilitated and integrated into decision-making processes. Elected members combine strategic responsibilities, oversight of statutory processes and ward and party representation. Ongoing democracy – interaction between elections through social media, neighbourhood level planning and web platforms such as Commonplace – challanges their role and the existing ways of arbitrating competing demands on resources (the key role of a local authority). The next step must be to debate these impacts with elected members and discuss how their role and relationship with the electorate might change. Given the typically very low turnouts in local elections, looking at the potential of “ongoing democracy” is an urgent task.

.png)